“Investigating the politics in participatory net art through The Core Project”

Introduction

The core can be described as the principal group of people forming the central part of a larger body, it is also the central part of an objects’ existence; fruit, seed, rock, planets and nuclear reactors all surround a core that houses the foundations of their structure. The Core Project, which I started in 2010, sits at the centre of my work, currently a curatorial practice influenced by anthropological research. The project asks one participant from each country in the world to film themselves responding to a question, the nature of which is only revealed to them once they have pressed record. The initial timeframe for the project was six months, however, it has been two years since it was begun and it is still ongoing. As the project unfolded difficulties arose. My initial aim of compiling an anthropological analysis of global artistic and political views, was hindered by difficulties in communications, politics and the scope of collating submissions from all countries. The results, regardless of whether all countries have a submission, will reveal more about the social and cultural factors effecting the project then the completion of the project could. This text will interrogate the project through an analysis of the elements that frame the piece, namely; socio-political engagements, economic factors, relationships between global visual art and digital culture. I will discuss the positioning of net art, new media art and net curation, as they sit within their own niche in contemporary art, all of which are at the heart of the project, due to their immateriality and global scope. Furthermore I shall examine how the engagement by the users of the medium is contingent on technological advances and influenced by cultural differences. Understanding the possible contexts of the users, or an online audience in participative systems, can allow both curators and net artists to interpret and negotiate cultural frameworks that may influence the users’ experiences. I will discuss how The Core Project is constructed by the participation of distinct players; at the centre the curator as the driving force behind the project and the selector of its participants. Subsequently the video participants or ‘sub-artists’[1] produce a video and thirdly the existence of the audience who will view the final piece. I will examine the role of this audience, while analysing how the participatory players produce changes through their engagement and experience as both sub-artists and spectators. I will conclude on the project’s political framework and its position in an online public sphere and space.

The Core Project

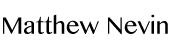

FIG 1: The Core Project, www.the-core-project.com

The aim of the project is to explore the fundamental opinions and political thoughts of participants from every country across the globe. By devising this project I wished to begin an investigation into the views of a wide variety of people. I decided to try to contact one person from every country in the world; a big undertaking however the process has itself become a dynamic part of the artwork. Titling it a ‘project’ rather than an artwork was deliberate. The project has a particular aim and is organised through developmental phases producing a progressive outcome. This can be compared to a ‘piece’ of work that may be objectified or completed in a shorter, more precise manner. The project logistically aims to involve the participation by one person in each sovereign, constituent or disputed state across the globe, as assigned by the United Nations list of member and non-member states (United Nations. 2012). The website (www.the-core-project.com) hosts instructions for the project, promotional material and will be home to the final piece on completion. As the curator I extensively search the Internet from country to country choosing participants through a nonpartisan criteria based on their interest in the project and the visual arts. These participants tend to be students, artists, academics and local government employees. It is these contributors that will then represent their country; they will produce a video replying to a question (the actual question is not revealed until after they have signed up) and submit it to me for inclusion. In the first instance I email the participant an initial set of instructions[2] that outline the rules of the project:

The video must:

- “Be no longer than two minutes in duration from when you hit record.

- At least contain one lead person, but can have more than one contributor.

- Be shot outside or part there of, to show countries exterior (such as through a window).

- Be one take, (No editing – except for the addition of sound if desired).

- Be Creative, Innovative, Bold, Adventurous, Different and Safe! Think about how and where you are going to film without knowing what you are going to be talking about!” (The Core Project, 2012).

These instructions provide the participant with an outline of the project and the procedures needed to take part as a contributor. Only once the camera is recording can the participants read the last page of the instructions that holds the secret question. If they are read this before the recording, the submission will not be accepted. I do not accept any premeditated answers. The last page of the instructions states:

“READ THIS (to yourself)

What is going to happen next?

NOW

CLOSE YOUR EYES FOR 10 SECONDS & THINK

NOW

SPEAK”

(The Core Project, 2012).

The intentionally vague nature of this question is deliberate, it aims to activate a moment which I call the ‘in-between’ phase. This ‘in-between’ phase (which lasts for ten seconds) is when the participant can be seen visualising his/her thought process, thinking what he/she is going to say in response to the question. It is an important component of the project. The participant’s immediate and spontaneous response to the question is of great significance to the project, as opposed to a well thought out and concise answer. This ‘in-between’ is the instance concerning the user’s deliberation of the unknown question and the identification with the moment of its reveal. The project’s procedures aim to trigger a moment of vulnerability, which is key to the process of engagement within the project and will become crucial in the viewership of the final piece. Furthermore the immateriality of this ‘in-between’ phase, which can be understood as the virtual commodification of emotion or reaction, becomes an element akin to the Internet’s concealed databases, servers, archives, software and code. While the combination of immateriality and projects physicality (video production) act as elements within the complex discipline of net art.

In his analysis of the role of the spectator in ‘The Emancipated Spectator’, Jacques Rancière described the traditional passive role of the spectator as a negative role. Rancière believed that becoming a spectator means looking as opposed to knowing or acting (Rancière, 2010). The appearance of looking while remaining motionless creates a passive spectator lacking any power of intervention. This traditional passivity of the spectator is what drove the convention of spectatorship. Through The Core Project I wish to challenge the role of passive spectatorship and provide an opportunity for the spectators to become active participants in a global intervention. This can be accomplished through new media art’s influence to push the boundaries of change in contemporary art. However change is not always accepted, as Walter Benjamin stated the “conventional is uncritically enjoyed, and the truly new is criticized with aversion”(2010, p.37). This notion is relevant to how new media art has allowed new technologies to revolutionize contemporary art, by bartering and diversifying the transgressions within spectatorship and participation. Jean Baudrillard takes this idea further in his work ‘Simulations’, when he questions our systems of interaction and communication, which he states has moved away from a complex structure of linguistics to a system of “question/answer-of perpetual test” (1983, p.116). The context of my curatorial decision in The Core Project is to focus on the participant’s procedure rather then a specific answer. It could therefore be argued that the participants of The Core Project become active spectators in the project, while contributing to a global communicative system.

3.0 Concept & Experience

The main aim of the instructions is to create conditions in which the participant speaks ‘within’ their moment in time and place, capturing a sense of the complexity and diversity of the nations that make-up our planet. The responses of early entrants from Afghanistan, Antarctica, Bahrain, Canada, El Salvador, Lesotho, Sweden and Tanzania have included participants speaking of political and social unrest, international politics, environmental change, or a reflection on their own personal lives. Locating the project online opens it to viewers from all corners of the globe and offers a partial insight into a life in each state. The project has witnessed problems since its inception, including a strong backlash from political anarchists in disputed territories/states. For instance, during the call for submissions for Abkhazia, I received emails from Georgians claiming it is not a country but a region of Georgia occupied by the Russian army. These complexities have arisen and continue to do so, however, if no response is received from any specific disputed territory then that state will not feature in the final project. These difficulties, the decisions on structure and the individual comments received from people all form part of the intricacies of the project.

What happens between the instructions and the actions of the participant (the procedures of the recording) is based within traditional engagements of video art. The participant operates and submits their part of the project, which includes an insight into their activities in their state. This is then transposed into the virtual world of online viewership. The correlation of the prescription (choosing of individual), action (recording) and reaction (online viewing) make up the processes of the project, all of which will be finalized within this virtual arena of the website. The delineation of the thought process is what prompted the creation of the piece. My aim was to try and expose and capture the user’s consciousness, transforming and representing their thoughts into a material existence in a globalized Internet art setting.

The Internet has become a public space to allow audiences to access a relative new public art form. Debra Benita examines how the Internet has enabled new politics in space, which can now be understood beyond public and private, facilitating the politics of “architechnological inconsistencies” to expose institutional control (Gunkel, 2011, p.253). Net art provides an opportunity to both artists and spectators to understand the accessibility of this digital public space, while it presents new challenges to both artists and curators within the public sphere. Net art can potentially be made available to anyone and everyone who can access the Internet. It is therefore an appealing platform for activists who are motivated by political participation through transnational exchanges. The Core Project aims to act as a force, influencing and creating new social responsibilities, contextualized by using connectivity to assert its cause. The Core Project is paradigmatic of what Joseph Beuys’ terms ‘social sculpture’, in that it outlines art’s ability to transform society, he believed art is capable of dismantling the negative paradigms in our social systems (Tisdall, 1974, p.48). The Core Project’s ultimate goal is to become a successful technological art endeavour that challenges societies’ perception of art and the power of its political agency. This will be accomplished by the project producing a transformation in showing the viewer that it is possible to connect societies through an international endeavour, an aspect that net art has become involved in.

Rancière suggests that the common power, which is understood to be from sharing a common space and concerns, is a binding intellectual factor, the mode of which enables individuals to control power through their own terms (Rancière, 2010). Over the past forty years, societies dominated by the power of capitalism have created a globalized interconnected world. The development of information technology and the sciences has facilitated an increase in communication technology enabling a shared digitized, media heavy culture. Furthermore, a new kind of information culture and a ‘society of the spectacle’ have emerged from post industrial capitalism (Debord, 1984). This has enabled tech savvy individuals to engross/retrieve and renew individual power, rather then input back into society. The Core Project aims to reassert some of the utopian aspirations of the early ideals of the Internet; a globally interconnected system transferring knowledge and power across boarders. The political and geographical issues that arise from the project such as the analysis of social conditions created by shifting sovereign boundaries, political unrest, and global networking, contribute towards a movement beyond the moment of recording.

Net art

Net art sits in the sub directory of the term new media art, the terminology of which is deeply contentious. New media art has pushed artists and curators of certain disciplines to revaluate the descriptive titling of their work. Beryl Graham in ‘Rethinking Curating Art after New Media’, shows just how complex the term new media art is, by listing the numerous disciplines/technologies it refers to:

“art & technology, art/sci, computer art, electronic art, digital art, digital media, intermedia, multimedia, tactical media, emerging media, upstart media, variable media, locative media, immersive art, interactive art, and Things That You Plug In” (Graham, 2010, p.4).

It could be argued that complexities, such as the importance out on labelling, are problems within a contentious artworld. Visitors to a gallery and website, or audience in a public art space will more likely be concerned with their experience of the art and not what label the curator or artist has put on his/her own work. I shall circumvent such conflicts as I shall now focus on the politics and understanding behind net art and The Core Project’s place within new media art.

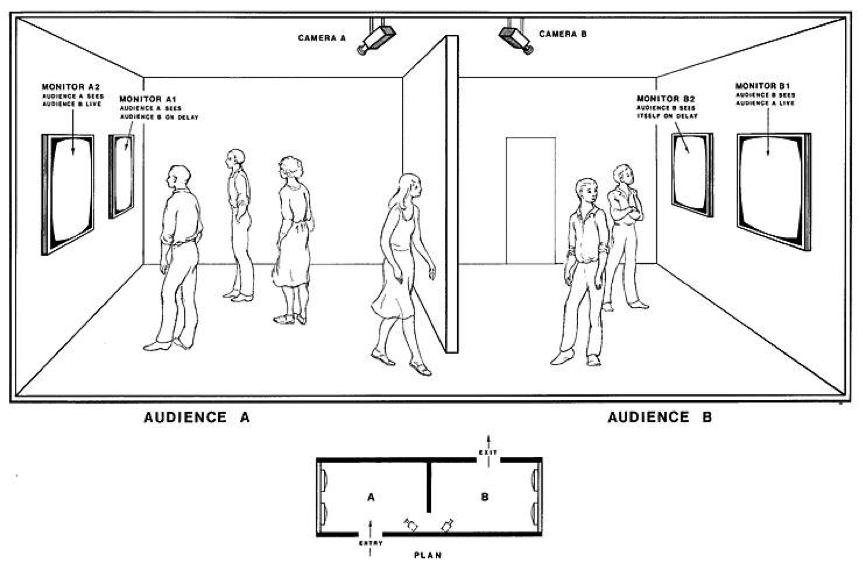

The computer has become both a tool and a host for art; software is replacing the physicality of some traditional art mediums. The process of visual transmission, interaction and participation in The Core Project can be traced back to ideas established in the 1970s by artists such as Dan Graham, Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway. Graham’s 1974 work Opposing Mirrors and Video Monitors on Time Delay (Figure 1) created an installation in an experiment of visual time delay, where he confused visitors through a series of mirrors, monitors and video surveillance.[3]

FIG 2: Dan Graham, Time Delay Room, 1974

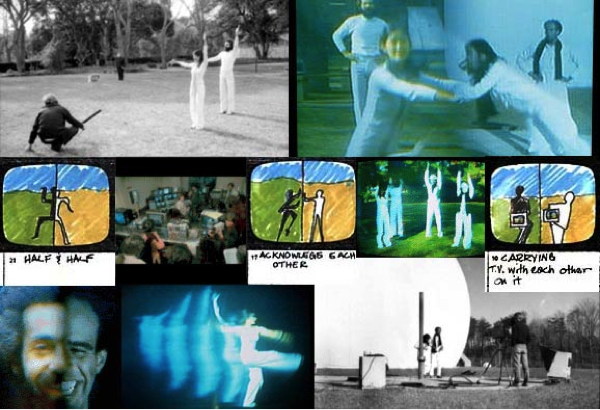

Dan Graham was one of the earliest video artists to explore the voyeuristic relations between video and the audience’s participation between visual time, architecture and transmission. In 1977 Galloway & Rabinowitz’s fascination with exploring alternative structures for video and television resulted in the creation of Satellite Arts Project: A Space with No Geographical Boundaries (Figure 2). This led to the world’s first interactive, composite-image satellite dance performance (Lovejoy, 2004). Live images were remixed to allow performers crossing geographical borders to dance together in a virtual exploration of space.

Figure 3: Satellite Arts Project: A Space with No Geographical Boundaries, 2012.

These projects, with the creation of the Internet, in time gave rise to the formation of net art, allowing projects such as The Core Project to break geographical boundaries. In order to analyse this claim we must first understand what net art can achieve. Rachel Greene describes it as an art form that intertwines technology, production and consumption. The decentralization within The Core Project and the Internet alters boundaries, allowing art practices the capability to reach new audiences and offers ways “to remix and revitalize categories often reified in the art world and beyond” (Greene, 2004. p.31). Net art is frequently focused on audience participation, whether it involves a simple click or more complex navigation through a website. The process behind its existence includes the output/input nature of the Internet and computer technology. The Internet has been challenged and obstructed by political issues, such as developing countries struggling to get online. Furthermore, countries such as China or North Korea are creating state imposed access restrictions and diverting government propaganda streams to its users (BBC, 2012). However, in countries where there are no such restrictions, net art functions relatively independently within a virtual public space.

Unlike other art mediums, net art does not rely on the physical space of the gallery for its presentation, and often when it is displayed within a gallery context, it is misrepresented. As it is not at risk of being commodified by the market, Joasia Krysa explains, in ‘Curating Immateriality’, net art calls for a ‘museum without walls’ while it my be open to interferences by its contributors, it is a space for exchange that is both transparent and flexible (Krysa, 2006, p.81). Consequently, net art has the ability to transform digital space, a public space that has become more malleable and open to its users then the physical institutional restrictions within museums, galleries, or other public arenas. However, the ultimate control over these opportunities lies firmly in the curation of the medium itself.

4.1 Net Curation

The role of the net curator is caught between two difficulties; its own self-establishment and its battle against net artists who are becoming self-curators. CONT3XT.NET considers that net curators are “ ‘cultural context providers’, ‘meta artists’, ‘power users’, ‘filter feeders’ or simple ‘proactive consumers’ ” (2007, p.6). They create discursive models that provide resources for net artists. The curation of The Core Project provides this through an analysis of cultural and relationship issues. The following examples of early online artist’s curatorial projects outline the development of net curation and the role it plays within both net art and new media art. In 1993, the Austrian artist Eva Grubinger developed ‘C@C’ Computer Aided Curating, which was an early example of a system of presentation and distribution of contemporary art online (Krysa, 2006, p.101). The project, which was set up in the infancy of the Internet, involved the participants creating a piece of their own work online and on completion they allocated three additional artists to the project. This created one of the first examples of a social network of artists displaying and creating work online. Additionally the artists Miltos Manetas and Peter Lunenfelt in 2002 took online curation to an activist level. Manetas, in a protest against not making the selection for the Whitney Biennial of that year, built a counter exhibition website called Whitneybiennial in order to divert traffic away from the genuine site. Manetas announced that he planned to use twenty-three U-Haul trucks equipped with projectors to stage a visual protest outside the Whitney Museum on the Biennials opening night. It did not happen, but instead a form of ‘performance’ occurred whereby audience members of the biennial claimed to have seen the U-Haul trucks, creating as Manetas states an artistic “urban legend” (Manetas, 2012.). However, Beryl Graham appropriately questioned, “was the entire project a conceptual breaking of boundaries between the virtual and real” (2010. p.254), which addressed the debate of artists working as curators. These pioneers in net curation pushed political and technological boundaries, while using net art as a form of resistance against the established art world. The self-organisation and collaboration between online artists and curators through technological networks, online systems, databases and programming, enabled net art to grow as its own autonomous medium.

However, the roles of artist and net curator intertwine differently when comparing net art to its physical visual art counterparts. Graham questions the comparison of curating an invisible system to an object by asking;

“if the curator is not curating an object but a ‘participative system’, then the invisible system itself needs to be thoroughly understood, not only by the curator, but also by the audience.” (Graham, 2010, p.124)

It is through an understanding of how these systems operate, that the roles of curator, artist and participant, can be designated. The complexities behind The Core Project operate as a participative system that negates physicality. The audience must fully comprehend its structure on completion, as they become participants and viewers of this immaterial system.

5.0.Participation

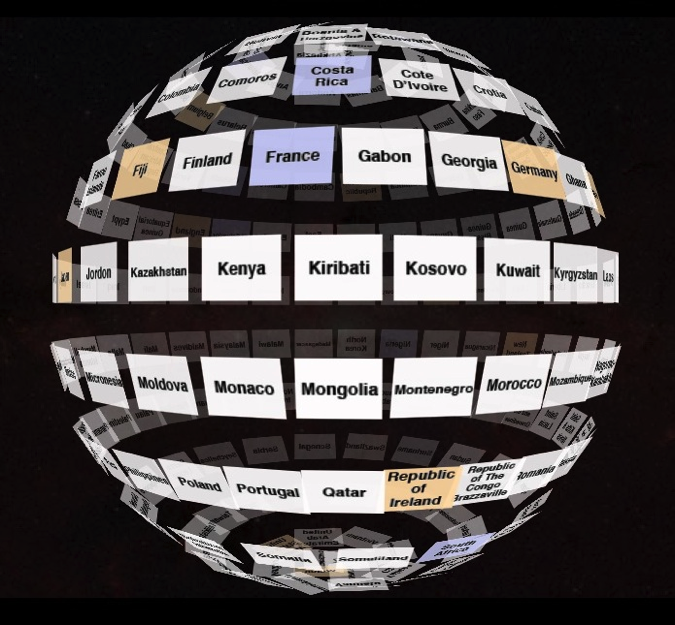

Figure 4: The Core Project Participants

If a curator is managing a system of participants, who engage as sub-artists, what are the accurate roles of the participants within this system? In The Core Project I convert myself from artist to curator and in turn the participants become sub-artists controlled within my system of rules, while the elements further contribute to the politics within participatory net art. This can be compared to the context of a traditional show where artists create work that the curator constructs into an exhibition for an audience to visit in a physical space. Nevertheless, the challenge remains to define the space or role each contributor provides. As a visual artist, I have fallen into a curatorial position, by producing the participants through a method of online prescription, which has in turn become one of the main barriers of the piece. The investigation and connection with suitable contributors has been quite difficult due to political and social issues causing restrictions. Such as the aforementioned Internet access, or local political agendas which affect participants inclusion. Once engaged, the participants become sub-artists whose role it is to follow the curator’s procedures. By completing their submission they negate their role as spectator and become performers. Rancière attributes this notion in his analysis of theatre, which can be transposed on to net art;

“what has to be pursued is a theatre without spectators, a theatre where spectators will no longer be spectators, where they will learn things instead of being captured by images and become active participants in a collective performance instead of being passive viewers” (Rancière, 2010).

As with theatre, The Core Project becomes a place where performative action engages artists, spectators and audience. The initial viewers of the piece become participants activating themselves in this collective performance, disavowing their role as spectators and becoming active contributors, in turn causing a vacuum, which is filled by the online audience. These new spectators will be able to engage directly with all the participants work through one portal – the website. The complexities of these procedures and role allocations are elements of the complex system of politics in net art.

These cultural systems within net art and other new media art often self damage by opposing reform, partly due to the instinctual behaviour of self-resilience and survival. Such resilience has led a considerable amount of net art to replace the passive consumption of the Internet with employed response. This instigates activity both online and in real life engagements, as within The Core Project activating both a global online endeavour and individual real world response. Utilizing emerging technology and activity, net art inspired artists in the 1970s to associate themselves with Tactical Media. A term associated with artwork that focuses on intervention, engagement and critique of the dominant political and economic order of society. This allows participants to become subjects (in this case sub-artists) and move away from singular spectatorship. Through this form of activation and collaboration, art online (in all forms) has become a collective creation process. Enabled by technology and the sharing of skill sets of artists, engineers and curators, all permitting the creation of art into a virtual form. Once within this form the work often becomes interactive, whether inside a software system, within itself, or directly with the viewer.

6.0 Politics in the Internet

The Core Project in essence is an online video art project prompted by political activism, a framework that has been embedded into my practice from an early stage. I shall now discuss the influence the Internet and net art has with the promotion and coordination of modern politics. The online movements such as the ‘Yes Men’; are a key example of a real/virtual activist group who have used the mainstream media and online resources to parody globalized corporations through interventions and activist performance art projects (Graham, 2010, p37). The foremost online activist and whistle-blower group ‘Wikileaks’ is undoubtedly the front-runner in online activism. Notably run by the Australian editor Julian Assange, who has been thrown into global disrepute and controversy by obtaining and releasing numerous international government documents, such as the prominent documents by soldier Bradley Manning. Manning became disillusioned from witnessing civilian causalities and atrocities carried out by his fellow soldiers and handed over documents that would see the USA government operations exposed to billions online. It would be pretentious to associate my work directly with the above but it is vital to highlight and acknowledge the prevailing power the Internet has begun to hold in political activism. The Core Project is not direct activism, but a deputized, democratic form of activism, that seeks to highlight the personalised issues of the participants, rather then pushing views upon them. The politics of working in digital participatory net art has become evident through the project’s development. There is a heightened digital and political awareness that has emerged in our society. From the outset, I decided to be as inclusive as possible and to pass the power decisions over to the participants. The Internet has become an effective tool to produce political power, in a manner in which the ‘real world’ political activism cannot. Increasingly, online petitions are taking over from protests, emails from letters, online videos from television, pod casts from radio. A fresh system of political existence has immerged facilitated by new digital cultures. Chantal Mouffe pushes for this to replace or hinder the negative effects of globalization;

“we want to prevent the consequences of globalization from being the imposition of a single homogenizing model of society and the decline of democratic institutions, it is urgent that we imagine new forms of associations in which pluralism could flourish and where the capacities for democratic decision could be enhanced” ( Mouffe, 2002, p.65).

Net art adopts Mouffe’s judgments through its new forms of associations; curator-artist, artist-participant, participant-spectator, which can be seen in The Core Project, all of which have transformed how art is visualised and received online. For instance the project aims to open up a new dialogue amongst nations through its trans global positioning. However the idea the Internet is an open platform of individual activity is quite idealistic. The risk net art produces in participatory culture is it begins to compete on the Internet with the noise and capitalism of popular media; such as the two powerhouses Google and Facebook both floating now on the US stock exchange. The Internet as a tool manipulates and informs our actions, as such, net art has been influenced by its properties. However net art does not exist alone but is surrounded by its tools, by the service it provides and the results it produces.

7.0 Conclusion

Throughout this text, I have examined the complexities within the social and political realities of net art. It is evident the procedures, existence and placement of the medium is sometimes not helped by its artists or curators, within the context of the visual arts. It is clear the Internet provides an opportunity for subcultures to mobilize their political participation and this is where I wish The Core Project to sit. The project has been placed as a backdrop to expose the role of the artist, curator, sub-artist and spectatorship of net art and its engagement with the audience. It is evident The Core Project has become a system of engagements that have direct influence with its sub-artists who may provoke political action through their video productions. I also have underlined the significant role the instigators in net art and net curation have had on the evolution of the medium. While The Core Project’s positioning and analysis in net art has brought clarity to the medium’s ability to transform and utilize digital space. An aim of this text is to stress net art’s occasional insularity and complex positioning within social-political agendas. By highlighting the political framework that holds the medium in a virtual public sphere, I have addressed the responsibilities held by the contributors and curators of the medium. It has become clear that the concepts behind its politics, spectatorship, participation and role in new media art have been significant within contemporary art debate. The progression and completion of The Core Project may take another few years, with almost two thirds of the collection of submissions yet to receive; there is undoubtedly a difficult road ahead.

Bibliography

Books:

BAUDRILLARD, J.,1983. Simulations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

BENJAMIN, W., 2010. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

CANDY, L., 2011. Interacting: Art, Research and the Creative Practitioner. UK: Libri Publishing.

CONT3XT.NET, 2007. Curating Media/Net/Art. 1st ed. Unknown: Books on Demand .

DEBORD, G., 1984. Society of the Spectacle. USA: Black & Red.

GRAHAM,B., COOK, S., 2010. Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

GREENE, R., 2004. Internet art (World of Art). London: Thames & Hudson.

GUNKEL, DJ., 2011. Transgression 2.0: Media, Culture, and the Politics of a Digital Age. 1st ed. London: Continuum.

KRYSA, J., 2006. Curating Immateriality (Data Browser). USA, Autonomedia.

LOVEJOY, M., 2004. Digital Currents: Art in the Electronic Age . 3rd ed. UK: Routledge.

TISDALL,C., 1974. Art into Society, Society into Art. ICA, London.

Articles/Chapters:

MOUFFE, C, 2002. Which Public Sphere for a Democratic Society?. Theoria, Vol 49, No. 99, pp.55-65.

STEMMRICH, G., 2002. Dan Graham. In: Thomas Y. Levin, Ursula Frohne, Peter Weibel, CTRL[SPACE] Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother, ZKM | Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, 2001, Cambridge, MA, London. The MIT Press.

Web Resources:

BBC. 2012. Cracks in the wall: Will China’s Great Firewall backfire?. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-17910953. [Accessed 08 September 12].

MANETAS, 2012. Whitneybiennial.com – the story.[ONLINE] Available at: http://www.manetas.com/eo/wb/files/story.htm. [Accessed 07 February 12].

RANCIÈRE, 2010. The Emancipated Spectator. [ONLINE] Available at:http://members.efn.org/~heroux/The-Emancipated-Spectator-.pdf. [Accessed 07 September 12].

THE CORE PROJECT, 2012. The Core Project. [ONLINE] Available at: http://the-core-project.com/thecoreproject-instructions-do-not-read-until-day-of-recording.pdf. [Accessed 07 September 12].

UNITIED NATIONS, 2012. Member States of the United Nations . [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.un.org/en/members/index.shtml. [Accessed 12 September 12].

List of Figures / Images:

Figure 1: THE CORE PROJECT, (2012). Screengrab [ONLINE]. Available at: http://www.the-core-project.com [Accessed 12 September 12].

Figure 2: GRAHAM, D., 2012. Dan Graham, Time Delay Room, 1974 [ONLINE]. Available at: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/assets/img/data/1807/full.jpg [Accessed 12 September 12].

Figure 3: SATELLITE ARTS PROJECT, 2012. A Space With No Geographical Boundaries, sat_arts_project2 [ONLINE]. Available at: http://1904.cc/aether/hist/sat_arts_project2.jpg [Accessed 12 September 12].

Figure 4: THE CORE PROJECT, (2012), The Core Project Participants [ONLINE]. Available at: http://www.the-core-project.com/screenshotsgroup-01.png [Accessed 12 September 12].

[1] I use the term ‘sub artist to denote a participant that plays a vital role in producing artistic material for the project.

[2] Please see The Core Project, 2012 in the bibliography for a link to the full instructions

[3] “Two rooms of equal size, connected by an opening at one side, under surveillance by two video cameras positioned at the connecting point between the two rooms. The front inside wall of each features two video screens – within the scope of the surveillance cameras. The monitor which the visitor coming out of the other room spies first shows the live behavior of the people in the respective other room. In both rooms, the second screen shows an image of the behavior of the viewers in the respectively other room – but with an eight second delay.” (Stemmrich,G. 2002.p.68)